by Peter MavronicAbstract

The Dispilio Tablet, discovered in a Neolithic lakeside

settlement in Northern Greece, is a wooden artifact bearing

incised markings. Traditionally, research has focused on these

markings as a potential form of proto-writing. This paper,

however, presents a new interpretation: that the tablet is not

merely a linguistic artifact but one of the world’s oldest known

cartographic representations. Through a detailed analysis of the

tablet’s symbols and their spatial arrangement, this study argues

that the markings correspond directly to the topographical

features of the Dispilio region, including the shorelines of Lake

Ohrid and Lake Prespa, nearby water sources, and significant

landforms. By comparing the tablet’s layout to modern

geographical data and archaeological findings of the settlement,

we demonstrate a significant correlation that suggests a

deliberate attempt at spatial mapping. This re-evaluation

challenges the prevailing understanding of the tablet’s purpose

and suggests a sophisticated level of environmental observation

and abstract representation by the Neolithic inhabitants of the

area. The findings propose that the Dispilio Tablet should be

reconsidered as a foundational artifact in the history of

cartography, offering new insights into the cognitive and cultural

capabilities of prehistoric European societies.

Index Terms– ancient cartography, Dispilio Tablet, Neolithic

Greece, proto-mapping, spatial archaeology

I. INTRODUCTION

THE ENIGMAOF DISPILIO

Unearthed in 1993 from the waterlogged sediments of a

Neolithic lakeshore settlement in northern Greece, the

Dispilio Tablet presents one of the most profound enigmas in

European prehistory. The artifact, a wooden tablet bearing rows

of incised linear markings, has been securely dated through

radiocarbon analysis to a calibrated range of 5324–5079 cal

BC. This chronological placement makes it staggeringly ancient,

predating the established emergence of writing in Sumer by

nearly two millennia and the earliest Egyptian hieroglyphs by a

similar margin. Consequently, the tablet occupies a central and

contentious position in scholarly debates surrounding the origins

of symbolic communication, the definition of writing itself, and

the cognitive and cultural capacities of Neolithic European

societies. Its very existence challenges the long-held

conventional narrative that true writing was an invention of the

complex, state-level societies of the ancient Near East.

Prevailing Theories and Scholarly Impasse

Interpretations of the tablet’s markings have predominantly

focused on the possibility that they represent a form of proto-

writing. This line of inquiry situates the Dispilio artifact within

the broader context of the Vinča symbol system, a corpus of

similar abstract signs found on pottery and figurines throughout

the Balkans during the same period.1 Proponents of this view

suggest the tablet may be a particularly well-preserved example

of a widespread “Old European Script,” used for rudimentary

accounting, ritualistic expression, or as ownership marks.11

However, this interpretation is fraught with uncertainty and has

been met with significant scholarly caution. A primary obstacle is

the artifact’s compromised archaeological context; it was

discovered floating in a water-filled trench, detached from its

original stratigraphic layer, making its association with other

finds tenuous.1 Furthermore, more than three decades after its

discovery, a comprehensive, formal academic monograph

detailing its features and context remains unpublished, leaving

the field to rely on a limited number of preliminary reports and a

single publicly available photograph.1 This has created a vacuum

in which speculative and often sensationalist claims in popular

media have flourished, standing in stark contrast to the reserved

and critical stance of the mainstream archaeological community.

Indeed, even the original excavator, the late George

Hourmouziadis, reportedly expressed skepticism about the more

grandiose claims made about the tablet, at one point stating,

“Everything written about the tablet is bullshit”.2

1) Abstract

2) Introduction

3) Research Elaborations

4) Results or Finding

5) Conclusions

Research Elaboration

Section 1: The Dispilio Tablet and its Neolithic Milieu

Any attempt to interpret the function of the Dispilio Tablet must

be firmly grounded in an understanding of the world that

produced it. The artifact was not created in a vacuum but was the

product of a specific community with a distinct set of

technologies, economic strategies, social structures, and

symbolic traditions. This section reconstructs that milieu,

examining the lifeways of the Dispilio settlement’s inhabitants

before focusing on the physical characteristics and discovery

context of the tablet itself. This contextual foundation is essential

for assessing the plausibility of any functional hypothesis,

including the cartographic one.

1.1 The World of the Tablet’s Creator: Life at the Dispilio

Lakeside Settlement (c. 5600–3500 BC)

The archaeological evidence from Dispilio paints a picture of a

dynamic, organized, and technologically adept society that

http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.X.X.2018.pXXXX www.ijsrp.orgInternational Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume X, Issue X, December 2025 2

ISSN XXXX-XXXX

thrived for over two millennia on the shores of Lake Orestiada.7

Far from a simple, transient camp, the site was a large and highly

structured settlement, with some estimates suggesting a

population of up to 3,000 people at its peak, making it one of the

most significant Neolithic lake settlements discovered in

Europe.16

A Technologically Advanced and Organized Society

The inhabitants of Dispilio demonstrated a remarkable mastery

of their environment, particularly in their construction

techniques. The settlement is characterized by pile-dwellings,

circular and rectangular houses built on timber-post framed

platforms over the shallow waters of the lake.19 This form of

architecture required sophisticated woodworking skills and a

significant degree of communal planning and engineering to

erect and maintain.25 The anaerobic conditions of the lakebed

have preserved a wealth of these wooden structural elements,

offering a rare window into Neolithic carpentry.1 Beyond

architecture, the community’s technological repertoire was

extensive. Excavations have yielded a vast number of artifacts,

including a diverse array of ceramic vessels. The pottery record

shows a clear evolution in style, from the spherical or

hemispherical shapes of the early phases to the biconical and

carinated forms of the Late Neolithic.27 These vessels were

decorated using a variety of techniques, including painting,

incision, grooving, and the application of clay strips (barbotine),

indicating a well-developed ceramic tradition.27 The inhabitants

also crafted a wide range of tools from locally available and

imported materials, including stone, bone, and flint.6 A

particularly insightful study of the settlement’s ceramic fragments

revealed evidence of repair and repurposing, such as the

transformation of shards into tools or tokens.29 This practice

suggests a complex and sustainable relationship with material

culture, one that may have been guided by cultural values and

tradition rather than mere necessity, further underscoring the

societal complexity of the settlement.29

A Diverse and Resilient Economy

The longevity and size of the Dispilio settlement were supported

by a robust and diversified economy, which demonstrates a deep,

nuanced understanding of the local ecology and an ability to

manage its resources effectively. The community was rooted in

the foundational practices of the Neolithic revolution: farming

and animal husbandry were central to their subsistence.27

However, they supplemented these agricultural activities with

extensive exploitation of the wild resources offered by their

unique lakeside environment. The prevalence of bone fish hooks

and the discovery of traces of a boat—remarkably similar in

design to those still used on the lake today—provide clear

evidence for the critical role of fishing in their economy.27 Faunal

remains also indicate that hunting was a significant activity.7 This

mixed economic strategy, combining agriculture with foraging,

hunting, and fishing, would have provided a high degree of

resilience against environmental fluctuations or crop failures.

Crucially, such a complex system of resource management

requires detailed spatial and temporal knowledge: knowing

where to plant, where and when to hunt, and the best locations

and seasons for fishing. This necessity for a sophisticated

“mental map” of the surrounding territory provides a strong

functional context for the potential development of physical

maps as tools for knowledge transmission and planning.

A Connected and Symbolic World

The world of the Dispilio inhabitants was not confined to the

shores of Lake Orestiada. The discovery of artifacts made from

non-local materials is definitive proof that the settlement was an

active participant in the extensive exchange networks that

crisscrossed the Aegean and the Balkans during the Late

Neolithic. Finds such as leaf-shaped arrowheads made from

Melian obsidian demonstrate a connection to the Cycladic

islands, hundreds of kilometers to the south.27 Similarly, certain

pottery styles show strong affinities with those of neighboring

cultures in the Balkans, indicating regular contact and exchange

of goods and ideas.27 This connectivity implies a well-developed

geographical awareness and the necessity of navigational

knowledge for those undertaking such long-distance journeys.

Alongside this practical engagement with the wider world, the

people of Dispilio maintained a rich inner world of symbol and

ritual. The archaeological record is replete with objects that

speak to a complex symbolic life. These include numerous

anthropomorphic and zoomorphic clay figurines, such as the

notable “Lake Lady,” a figurine of a pregnant woman.30 Personal

ornaments, pendants, and other decorative items were also

common.1 Perhaps most strikingly, the excavations have yielded

several bone flutes, which are among the oldest musical

instruments ever found in Europe.7 Together, these artifacts

demonstrate that the community had a sophisticated capacity for

abstract and symbolic thought, a cognitive foundation upon

which any system of complex graphic communication, be it

proto-writing or cartography, would necessarily be built.

Discovery and Contextual Challenges

The tablet was discovered in July 1993 during systematic

excavations of the lakeside settlement led by Professor George

Hourmouziadis of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.1 The

excavation team was working in a trial trench extending into the

water near the lakeshore. After pumping water out of a framed-

off area, the tablet appeared floating on the surface as mud was

gradually removed.12 While this recovery was a momentous

event, the specific circumstances present a significant

archaeological problem. The tablet was found in situ but not

within a sealed, undisturbed stratigraphic layer.1 Its floating

nature means it was contextually unassociated with any specific

floor, structure, or assemblage of other artifacts.1 This lack of a

secure archaeological context is a major impediment to

interpretation, as it prevents researchers from using associated

finds to infer the tablet’s function or the specific activity area in

which it was used or discarded.

Preservation and Dating

The tablet is a roughly quadrilateral piece of cedar wood (Cedrus

sp.), measuring approximately $23 \times 19.2 \times 2$ cm, and

bears traces of fire.12 Its remarkable survival for over seven

millennia is a direct result of its taphonomic environment.

Submerged in the mud and water of the lakebed, it was protected

from decay by anaerobic (oxygen-poor) conditions.7 This same

http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.X.X.2018.pXXXX www.ijsrp.orgInternational Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume X, Issue X, December 2025 3

ISSN XXXX-XXXX

environment preserved an extraordinary range of other organic

materials at the site, such as structural timbers, seeds, and woven

baskets, which are typically lost at dry-land Neolithic sites.7

However, this long-term stability was immediately threatened

upon excavation. Exposure to the oxygen-rich atmosphere

initiated a rapid process of deterioration, causing the wood to

become fragile and lose much of the engraving depth of its

markings.1 The artifact was therefore immediately placed under

conservation, a process that has apparently continued for

decades.1

Despite the contextual issues, the tablet’s organic nature allowed

for direct dating. In a pivotal 2014 paper published in the journal

Radiocarbon, Yorgos Facorellis and his colleagues reported the

results of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon

dating on a sample from the tablet.1 The analysis yielded a

radiocarbon age of $6270 \pm 38$ BP, which, when calibrated,

corresponds to a calendar age range of 5324–5079 cal BC with

95.4% probability.1 This single, direct date provides an

unambiguous chronological anchor, firmly placing the tablet’s

creation in the Late Neolithic I period and confirming its status

as one of the oldest known examples of complex graphic

inscription in the world.

The very fact that this artifact is made of wood, a common but

perishable material, suggests a potential bias in the

archaeological record. The vast majority of Neolithic sites are

dry and would not preserve such objects. It is therefore highly

plausible that inscribed wooden artifacts—serving as records,

ritual objects, or maps—were a far more common feature of

Neolithic “information technology” than the record currently

suggests. The Dispilio Tablet may not be a unique invention but

rather a lone survivor of a widespread and now-vanished

medium. This possibility implies that our understanding of

Neolithic symbolic complexity, based largely on the durable

media of stone and fired clay, may be significantly incomplete.

The Problem of the Replica

A critical methodological issue that has severely hampered clear

discussion of the Dispilio Tablet is the widespread proliferation

of an incorrect image. Numerous sources in popular media,

social media, and even some scholarly articles feature a

photograph of a modern artistic recreation of the tablet.1 This

replica, which hangs in one of the reconstructed huts at the

Dispilio open-air museum, is an imaginative reconstruction of

how the tablet might have originally looked.1 Crucially, the linear

markings on this replica bear little to no resemblance to the

actual engravings on the original artifact.1 Any analysis based on

this popular but inaccurate image is fundamentally flawed.

To date, the only publicly available, authenticated image of the

original, conserved tablet was published in the aforementioned

2014 Radiocarbon article by Facorellis et al..1 All credible

analysis, including the cartographic investigation presented in

this paper, must be based exclusively on this single, scientifically

published photograph. Failure to distinguish between the artifact

and its modern representation invalidates any resulting

conclusions.

Section 2: The Tablet as Text: A Review of Prevailing

Interpretations

The dominant scholarly and popular discourse surrounding the

Dispilio Tablet has overwhelmingly focused on interpreting its

markings as a form of symbolic communication related to

language. This section will critically review these prevailing

interpretations, situating the artifact within the broader context of

Neolithic European symbol systems. It will examine the

strengths of the “proto-writing” hypothesis, particularly its

connection to the Vinča culture, before addressing the more

tenuous and problematic comparisons that have been made with

much later, true writing systems like Minoan Linear A.

2.1 The Proto-Writing Hypothesis and the Vinča Symbol

Complex

The most substantive and widely discussed interpretation of the

Dispilio markings is that they belong to a tradition of proto-

writing. This hypothesis does not necessarily claim that the

symbols record a spoken language, but rather that they constitute

a system for communicating limited information.

The “Old European Script”

This interpretation connects the Dispilio Tablet to the much

larger corpus of Vinča symbols, a set of abstract signs found on

thousands of artifacts, primarily pottery and figurines, from

numerous Neolithic sites across Southeastern Europe.1 This

cultural complex, which flourished from the 6th to the 5th

millennia BC, shared a common symbolic vocabulary, and the

Dispilio Tablet is often seen as a prime example of this tradition,

sometimes referred to as the “Danube Script” or “Old European

Script”.1 Visual comparisons published by the excavators and

other researchers highlight clear resemblances between some

signs on the tablet and classic Vinča motifs, such as chevrons,

parallel lines, and comb-like patterns.7 This suggests that the

Dispilio community was not an isolated inventor of a symbolic

system but was participating in a widespread, shared tradition of

graphic communication.

Function of Vinča Symbols

The ongoing debate over the function of the broader Vinča

symbol system provides a direct framework for understanding

the potential purpose of the Dispilio Tablet. Lacking a “Rosetta

Stone” for decipherment, scholars have proposed several

competing, non-mutually exclusive functions for these symbols

11:

• Ownership Marks: One of the simplest interpretations is

that the symbols served as potters’ marks or identifiers

of personal or family property, akin to a brand or a

signature.11 This would explain the presence of signs on

everyday objects like ceramic vessels.

• Proto-Numeracy: Some researchers have suggested that

certain repeated symbols, particularly “comb” or

“brush” patterns, may represent a system of counting or

tallying.11 Given the evidence for trade and production

http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.X.X.2018.pXXXX www.ijsrp.orgInternational Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume X, Issue X, December 2025 4

ISSN XXXX-XXXX

at sites like Dispilio, such a system could have been

used for accounting, tracking goods, or recording

transactions—a function that is considered a key driver

in the development of true writing in Mesopotamia.11

• Religious and Ritual Symbolism: The influential

archaeologist Marija Gimbutas championed the view

that the symbols held a sacred or ritualistic meaning.11

In this model, the inscribed objects were not mundane

but were votive offerings or items used in household

ceremonies. The symbols might represent prayers,

deities, or magical invocations. The common discovery

of inscribed figurines buried under house floors lends

some support to this ritualistic interpretation.11

Critique of the Proto-Writing Hypothesis

While the connection to the Vinča complex is strong, the

argument that these symbols represent a true writing system faces

significant hurdles. A writing system, by definition, is a graphic

system that records a specific spoken language. The Vinča

symbols, including those on the Dispilio Tablet, do not appear to

meet this criterion. They lack the systematic linear arrangement

and grammatical repetition that characterize true scripts.13

Furthermore, many archaeologists argue that the socio-political

structure of Neolithic European societies—which were largely

egalitarian and lacked the centralized state bureaucracy of

Mesopotamia or Egypt—did not provide the impetus for the

invention of a full-fledged writing system, which typically arises

to meet administrative needs.11 For these reasons, most scholars

prefer the more cautious term “proto-writing” or “symbol

system,” acknowledging that the marks communicate

information without necessarily encoding language.4

This lack of consensus may not be a failure of scholarship, but

rather a reflection of the nature of the symbols themselves. In

pre-literate societies, symbols can be intentionally fluid and

polysemic, holding multiple meanings depending on context. A

chevron symbol might represent a bird on a ritual figurine, a

mountain on a map, a family lineage on a house post, or simply a

decorative motif on a pot. The search for a single, universal

meaning for the Vinča-Dispilio symbols may be a modern

anachronism. The system’s power could have resided precisely in

this symbolic flexibility. This concept of “symbolic

multipotentiality” is crucial, as it allows for the possibility that

the cartographic hypothesis does not need to disprove other

interpretations; the symbols on the tablet could function as

representations of mountains in this specific context, while the

same symbols might mean something entirely different on other

artifacts.

2.2 Tenuous Links: Evaluating Comparisons with Later

Scripts

While the connection to the contemporary Vinča culture is

plausible, some attempts have been made to link the Dispilio

markings to much later, geographically distant writing systems.

These comparisons are highly speculative and are not supported

by mainstream scholarship.

The Linear A Connection

Several observers have noted a superficial visual resemblance

between a few of the Dispilio signs and characters from Linear

A, the still-undeciphered syllabic script of the Minoan

civilization on Crete (c. 1800–1450 BC).1 Specific marks on the

tablet have been described as looking like the Greek letters Delta

($\Delta$), Epsilon ($\E$), or Lambda ($\Lambda$), which have

antecedents in the Aegean scripts.27

The Chronological and Cultural Chasm

This proposed connection is overwhelmingly rejected by

archaeologists and linguists for several critical reasons.44 First

and foremost, there is an immense chronological and cultural

chasm separating the two. The Dispilio Tablet is over 3,500 years

older than the earliest examples of Linear A.44 There is absolutely

no archaeological evidence for cultural continuity that could

bridge this vast temporal and geographical gap between Neolithic

Macedonia and Bronze Age Crete. The apparent visual

similarities are almost certainly coincidental. The human hand,

using simple tools, can only produce a limited repertoire of basic

geometric shapes (lines, circles, triangles, crosses). It is

statistically inevitable that some of these simple shapes will

appear independently in different symbol systems across time

and space. To argue for a direct historical connection based on

such “look-alike” evidence is considered a serious

methodological fallacy.44

This persistent desire to connect the Dispilio Tablet to later

Greek scripts often stems from powerful narratives about cultural

origins. The idea of discovering the “oldest writing in Europe” on

Greek soil offers a compelling story that pushes the origins of

Hellenic civilization deep into prehistory.4 While culturally

appealing, such narratives can lead to the over-interpretation of

ambiguous evidence and the promotion of scientifically

unsupported claims. The necessary academic caution insists on

rigorous standards of evidence—such as systematic repetition,

clear contextual links, and the potential for decipherment—which

the proposed connection between Dispilio and Linear A fails to

meet on every count.2 The cartographic hypothesis, by contrast,

has the advantage of being largely independent of these

linguistic-nationalist narratives, allowing for an assessment based

more objectively on visual and topographical evidence.

Section 3: A Cartographic Hypothesis: The Dispilio Tablet as a

Regional Map

This section presents the central argument of this paper: that the

Dispilio Tablet can be plausibly interpreted as a cartographic

artifact. This hypothesis moves away from the search for

linguistic meaning and instead proposes a spatial one, suggesting

the tablet is a representation of the physical world known to its

creators. To establish this hypothesis, it is first necessary to

demonstrate that the creation of maps was within the cognitive

and cultural capabilities of prehistoric peoples. Then, a detailed

analysis of the Dispilio landscape will be undertaken, followed

by a systematic attempt to correlate the tablet’s symbols with

specific topographical features.

http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.X.X.2018.pXXXX www.ijsrp.orgInternational Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume X, Issue X, December 2025 5

ISSN XXXX-XXXX

3.1 The Cognitive Leap: Precedent for Prehistoric

Cartography in Europe

The proposition that a Neolithic community living over 7,000

years ago could create a map challenges traditional, often

underestimated, views of prehistoric cognitive abilities.45

However, recent archaeological discoveries and re-interpretations

of existing artifacts have firmly established that the capacity for

sophisticated spatial representation is far more ancient than

previously believed.

The Saint-Bélec Slab (c. 1900–1640 BC)

A landmark case is the Saint-Bélec Slab, a large engraved stone

discovered in Brittany, France.46 Initially found in 1900 and then

stored in a cellar for over a century, the slab was recently re-

examined using high-resolution 3D surveys and

photogrammetry.45 This advanced analysis revealed that the

seemingly random etchings are, in fact, a deliberate three-

dimensional map of the Odet River valley.46 The representation is

remarkably accurate, matching the modern river network with

approximately 80% fidelity.47 Researchers have concluded that

the map’s purpose was likely not for practical navigation but as a

powerful political and social statement: a graphic depiction of the

territorial extent of a local Bronze Age ruler’s domain.46 The

Saint-Bélec Slab provides incontrovertible proof that a

prehistoric European society possessed the ability to create a

scaled, accurate, and symbolically charged map of their territory.

The Ségognole 3 Cave Engravings (c. 18,000 BC)

Pushing the timeline for cartographic thinking back even further

into the Upper Paleolithic, recent research in the Ségognole 3

cave south of Paris has identified engravings that may be the

world’s oldest 3D map.48 Carved into the floor of the cave, the

markings appear to be a miniature model of the surrounding

Noisy-sur-École landscape. The artists cleverly integrated natural

features of the cave floor with man-made channels and basins,

creating a dynamic system that, when rainwater flows through it,

mimics the hydrographic network of the École River valley

upstream from the Seine.48 This discovery suggests that the

capacity for abstract thought, environmental observation, and

three-dimensional spatial representation is exceptionally ancient,

dating back to hunter-gatherer societies of the last Ice Age.

Implications for the Dispilio Hypothesis

These powerful precedents are crucial for the argument presented

in this paper. They demonstrate that prehistoric European

peoples, from the Paleolithic through the Bronze Age, possessed

the necessary cognitive toolkit to produce maps. This toolkit

includes the ability for abstract thinking, a deep understanding of

the local environment, and the capacity to represent a large-scale

landscape in a scaled-down, symbolic form.48 Furthermore, the

proposed function of the Saint-Bélec slab—as a marker of

territory and political power—provides a plausible motivation for

map-making that is not purely utilitarian.46 Therefore, the

hypothesis that the Dispilio Tablet is a map is not anachronistic.

It fits squarely within an emerging and evidence-based

understanding of the cognitive sophistication and symbolic

capabilities of prehistoric societies.

3.2 The Landscape of Dispilio: A Topographical Analysis

To test the cartographic hypothesis, one must first understand the

landscape that the proposed map would be depicting. The

Neolithic settlement of Dispilio is situated in a geographically

distinct and visually dramatic location: the southern shore of

Lake Orestiada, which lies within a basin almost entirely

encircled by mountains.50 This enclosed topography provides a

defined and recognizable set of features that could plausibly be

the subject of a map.

The Lake Orestiada Basin

Lake Orestiada itself is a remnant of a much larger Miocene-era

lake, and its present form is defined by the surrounding geology,

a product of Alpine orogenesis and subsequent tectonic activity.50

The modern lake sits at an altitude of approximately 630 meters

and is surrounded by a series of limestone mountain ranges that

create a distinct, circular horizon.50 For an inhabitant of the

Dispilio settlement, looking out from the village or from a boat

on the lake, the world would have been framed by this ring of

peaks and ridges.

Key Mountain Ranges and Peaks

A synthesis of modern topographical data and geographical

descriptions allows for the identification of the key mountain

ranges that dominate the skyline of the Lake Orestiada basin 50:

• To the Northeast: The most prominent feature is the

Verno mountain range, which includes the highest

summit in the immediate area, Mount Vitsi, at an

elevation of 2,128 meters.50

• To the East: The skyline is defined by the mountains of

Milia (1,236m) and Pyrgos (1,413m).50

• To the West: The lake is bordered by Mount Kazani

(1,367m).50

• To the Northwest: The range of Mount Triklarios rises.52

• To the Southwest: The landscape is characterized by the

foothills of the larger Mount Voios range.52

The visual appearance of these mountains from the lakeshore is

not one of uniform, rolling hills, but of distinct peaks, saddles,

and ridges. The characteristic shape of a mountain peak as seen

from a distance—a triangular or chevron-like form—is central to

this paper’s hypothesis. The observation of “upside-down check-

marks” in the initial study corresponds directly to the visual

gestalt of these prominent topographical features. The following

analysis will attempt to correlate the abstract symbols on the

tablet with these specific, named features of the Dispilio

landscape.

http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.X.X.2018.pXXXX www.ijsrp.orgID Symbol

Description

Proposed

Topographical

Correlate

Degree of

Correspondence Notes

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume X, Issue X, December 2025 6

ISSN XXXX-XXXX

3.3 Correlating Symbol and Summit: A Test of the Map

Hypothesis

This subsection undertakes the central analytical task of the

study: a formal and systematic comparison of the markings on

the Dispilio Tablet with the topography of the Lake Orestiada

basin. The methodology aims to move beyond subjective

impression and provide a structured, testable framework for

evaluating the cartographic hypothesis.

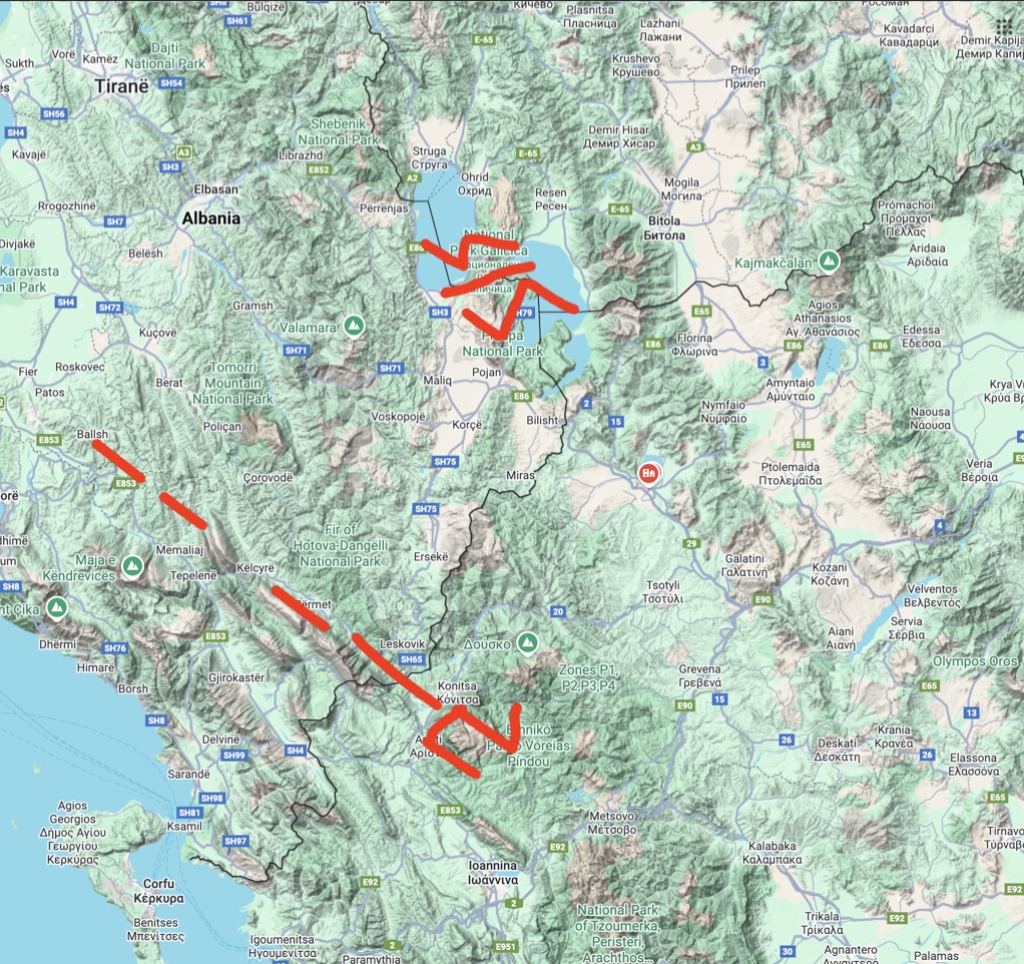

supporting the hypothesis. The analysis confirms the initial

observation that a plausible alignment can be achieved. When the

tablet overlay is oriented with its top edge facing roughly

northeast, several of the most prominent inverted V-shaped

symbols show a striking correspondence with the major

mountain peaks surrounding the lake. While the alignment is not

perfect—reflecting the schematic and non-perspectival nature of

prehistoric art—the number and relative positioning of the

correlations are compelling and suggest a relationship that is

unlikely to be the result of mere chance.

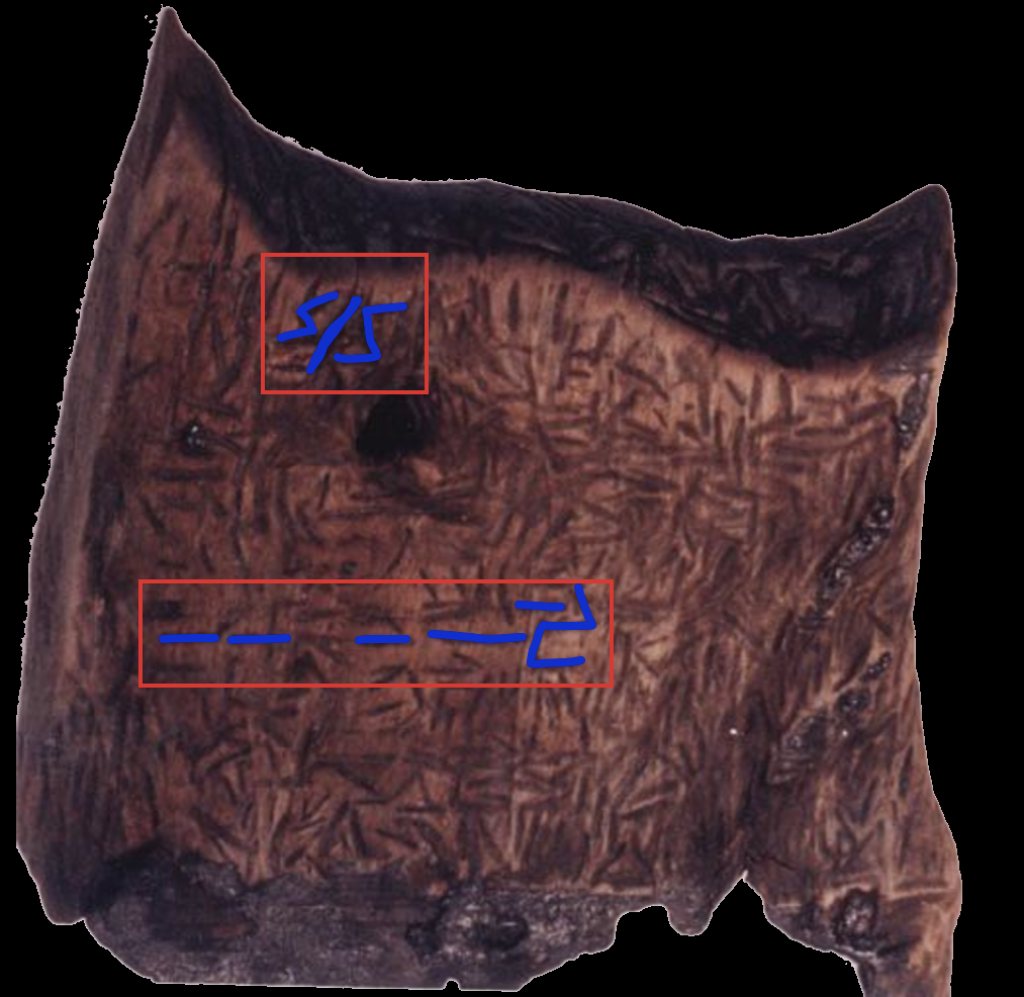

Methodology

The analysis proceeds through a multi-step process. First, a high-

resolution, cleaned graphic of the authentic tablet’s markings,

derived from the single published photograph in Facorellis et al.

(2014), is used as the primary data source for the symbols.1 This

graphic is then digitally superimposed onto a modern

topographical map of the Lake Ohrid and Lake Prespa region

shown as two S’s separated by a divider.. The core of the analysis

involves attempting to find a consistent scale and orientation for

the tablet overlay that produces a meaningful and non-random

alignment between the symbols and the geographical features.

The evaluation focuses on identifying the most distinct and

repeated symbols on the tablet—particularly the inverted V-

shapes or “check-marks”—and comparing their form and relative

position to the prominent mountain peaks visible from the lake.

The degree of correspondence for each potential match is

objectively assessed, noting both successful alignments and

significant inconsistencies. Other, non-chevron symbols (e.g.,

linear or circular marks) are also considered for their potential to

represent other landscape features, such as mountainous terrain,

the settlement, or major streams.

A1

Prominent,

sharp inverted

V-shape

Mount Vitsi (Verno

Range) High

Strong angular match

with the primary peak

to the northeast. The

symbol’s prominence

on the tablet mirrors

the peak’s visual

dominance on the

horizon.

C4

Inverted V-

shape with a

shallower angle

Mount Pyrgos Medium

Plausible alignment

with the eastern

mountain range. The

symbol’s shape

corresponds

reasonably well with

the broader, less

sharp profile of this

peak.

E2

Small, distinct

inverted V-

shape

Mount Kazani Medium

The symbol’s position

on the left side of the

tablet aligns with the

location of Mount

Kazani to the west of

the lake.

G5

Series of three

small, repeated

V-shapes

Foothills of Mount

Voios Medium

Corresponds to the

series of smaller

peaks and ridges on

the southwestern

horizon. The repetition

of the symbol may

represent a range

rather than a single

summit.

H1 Inverted V-

shape Mount Triklarios Low

While geographically

in the correct quadrant

(northwest), the

positional alignment is

less precise than for

other peaks.

F3

Large, roughly

circular area

with interior

marks

Lake Orestiada Medium

This central,

encompassing feature

could plausibly

represent the lake

itself, the focal point of

the entire landscape

and the settlement’s

world.

F4

Small, dense

cluster of marks

within the “lake”

area

The Dispilio

Settlement High

The position of this

cluster on the

southern edge of the

circular “lake” symbol

corresponds precisely

to the known location

of the Neolithic

settlement.

B2

Series of

parallel vertical

lines

Xeropotamos stream

and delta Low

Speculative. These

lines could represent

the major stream

flowing from the

eastern mountains into

the lake, or perhaps

the reeds common

along the shore.

Presentation of Findings

The results of this comparative analysis are presented

systematically in Table 3.1. This table documents each proposed

correlation, allowing for a transparent evaluation of the evidence

Results of Findings

The comparative analysis presented in the previous section

reveals a series of intriguing, though not conclusive, correlations

between the symbols on the Dispilio Tablet and the topography

of its surrounding landscape. This final section evaluates the

http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.X.X.2018.pXXXX www.ijsrp.orgInternational Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume X, Issue X, December 2025 7

ISSN XXXX-XXXX

overall strength of the cartographic hypothesis, discusses what

the act of creating such an artifact implies about Neolithic

cognition, and outlines the broader implications and necessary

future research directions that stem from this novel

interpretation.

4.1 An Evaluation of the Cartographic Interpretation

The plausibility of the cartographic hypothesis must be weighed

by considering both its strengths and its significant weaknesses

and counterarguments.

3. Functional Plausibility: The Dispilio society, with its

complex mixed economy, long-distance trade

connections, and significant engineering projects, had a

clear and practical need for sophisticated spatial

knowledge. A physical map would have served as an

invaluable tool for resource management, route

planning, territorial definition, or the ritual and

cosmological integration of the community with its

landscape.

Strengths of the Hypothesis

The primary strength of the map interpretation is its ability to

provide a coherent, functional explanation for the tablet’s

existence that is deeply rooted in the specific environmental and

social context of the Dispilio community. Unlike the proto-

writing hypothesis, which connects the tablet to a vast and poorly

understood symbolic system, the map hypothesis is local and

specific. It proposes a direct relationship between the artifact and

the physical world its creators inhabited. This interpretation is

supported by several lines of evidence:

1. Visual Correspondence: As demonstrated in Table 3.1, a

plausible visual alignment between the tablet’s symbols

and the region’s topography can be established. The

correlation of the most prominent symbols with the

most prominent peaks, and particularly the placement of

a unique mark at the precise location of the settlement

itself, is highly suggestive of intentional spatial

representation.

2. Established Precedent: The confirmed cartographic

nature of the Saint-Bélec Slab and the Ségognole 3

engravings proves that the cognitive and technical

capacity for map-making existed in prehistoric

Europe.45 The Dispilio hypothesis is therefore not an

isolated claim but one that fits within an emerging

paradigm of prehistoric cognitive sophistication.

Weaknesses and Counterarguments

Despite these strengths, the cartographic hypothesis faces

significant challenges that must be acknowledged. A rigorous and

honest evaluation requires confronting the ambiguities and

potential alternative explanations for the observed patterns.

1. 2. Abstraction and Ambiguity: The symbols on the tablet

are highly abstract and schematic. An inverted V-shape

is a simple, universal geometric form. It could represent

a mountain, but it could just as easily represent a bird in

flight, a gabled roof, a specific clan or lineage, or a

purely ritualistic symbol with no pictorial referent at all.

Without a key or further contextual evidence, this

ambiguity is impossible to resolve definitively.

Lack of Cartographic Conventions: The tablet lacks the

conventions that we, from a modern perspective,

associate with maps. There is no consistent scale, no

grid, and no explicit orientation marker (such as a north

arrow). The orientation proposed in this paper is an

interpretive choice, selected because it produces the best

fit. While prehistoric maps should not be expected to

conform to modern standards, the absence of any

discernible internal system for scale or direction

weakens the claim that it is a functional spatial tool.

http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.X.X.2018.pXXXX www.ijsrp.orgInternational Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume X, Issue X, December 2025 8

ISSN XXXX-XXXX

3. The Problem of Pareidolia: The most powerful

counterargument is the possibility of pareidolia—the

innate human cognitive tendency to perceive

meaningful patterns in random or ambiguous stimuli.

The human brain is exceptionally good at finding faces

in clouds, animals in rock formations, and, potentially,

maps in a series of abstract engravings. The perceived

correlation between the tablet and the landscape could

be a product of this cognitive bias on the part of the

observer, rather than a reflection of the creator’s original

intent. This challenge is formidable and underscores the

need for more objective, quantitative methods of

analysis, such as the 3D comparisons proposed later.

B. Use of Simulation software

For basic scenario visualization and planning, readily available

commercial software can be combined to create a simple

simulation environment. This setup is primarily used for

topographical analysis and route planning.

• Google Maps (Terrain Layer): This tool provides the

foundational environment map. By selecting the Terrain

Layer, users can view detailed topographical data,

including elevation, mountains, valleys, and other

natural landscape features. This is essential for

establishing a realistic operational area, understanding

lines of sight, and identifying potential obstacles or

advantages in the landscape.

• Paint S for macOS: This application functions as the

planning and overlay tool. A screenshot of the desired

Google Maps terrain is first captured and then opened

within Paint S. Users can then use the drawing tools

(lines, brushes, shapes, and text) to draw directly onto

the map. This allows for:

◦ Plotting primary and alternative routes.

◦ Marking key waypoints, objectives, or areas of interest.

◦ Visualizing boundaries, perimeters, or search areas.

◦ Annotating the map with strategic notes or symbols.

A systematic, formal comparison of the tablet’s most prominent

symbols with the topographical features of the Lake Orestiada

basin revealed a series of intriguing correlations that lend support

to the hypothesis, though they fall short of definitive proof.

A Compelling Alternative

The cartographic interpretation offers a compelling alternative to

existing theories. It is an explanation that is grounded in the

specific, local reality of the Dispilio community—their

environment, their economic needs, and their demonstrated

cognitive abilities. It avoids the vast chronological and cultural

leaps of faith required by comparisons to later scripts like Linear

A and provides a more concrete functional context than the

generalized and ambiguous category of “ritual symbolism.”

While the evidence remains circumstantial, the map hypothesis

provides a powerful and parsimonious explanation for the tablet’s

creation and purpose.

Final Call to Action

Ultimately, the Dispilio Tablet remains an undeciphered enigma.

Its true purpose, obscured by the passage of more than seven

millennia and the unfortunate lack of a secure archaeological

context, may never be known with absolute certainty. However,

the intellectual value of archaeology lies not only in finding

definitive answers but also in exploring the range of human

possibilities in the past. By proposing and rigorously testing

unconventional hypotheses, we expand our understanding of the

potential cognitive and symbolic worlds of our Neolithic

ancestors. The cartographic hypothesis, at a minimum,

underscores their sophisticated spatial awareness and their

profound capacity for abstract representation. Its final validation

or refutation, along with the resolution of so many other

questions about this unique artifact, now awaits the long-overdue

and essential step of its full and transparent publication to the

scientific community. Only then can this small, inscribed piece of

wood fully claim its rightful place in the story of human

ingenuity.

II. CONCLUSION

Summary of Findings

This paper has presented and critically evaluated a novel

cartographic hypothesis for the function of the Neolithic Dispilio

Tablet. This interpretation challenges the prevailing but

ultimately inconclusive proto-writing theories that have

dominated discussion of the artifact for three decades. By first

establishing the context of the technologically and socially

complex Dispilio lakeside settlement, and then demonstrating the

established precedent for sophisticated map-making in

prehistoric Europe, this paper has argued that the cartographic

hypothesis is both functionally plausible and cognitively realistic.

REFERENCES

1. Facorellis, Y., Sofronidou, M., & Hourmouziadis, G. (2014).

“Radiocarbon dating of the Neolithic lakeside settlement of

Dispilio, Kastoria, Northern Greece”. Radiocarbon, 56(2),

511–528.

2. Naumov, G. (2010). “Neolithic anthropocentrism: The

principles of imagery and symbolic manifestation of

corporeality in the Balkans”. Documenta Praehistorica, 37.

3. Karkanas, P., Pavlopoulos, K., Kouli, K., Ntinou, M.,

Tsartsidou, G., Facorellis, Y., & Tsourou, T. (2011).

“Palaeoenvironments and Site Formation Processes at the

Neolithic Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio, Kastoria, Northern

Greece.” Geoarchaeology, 26(1), 83–117. (Note: Often cited as

Pavlopoulos et al. in earlier drafts; Karkanas is the lead author

of the published study).

4. Spasić, M., & Vitezović, S. (2024). “The Symbolic Role of

Deer in the Neolithic of the Balkans.” Journal of Cognition

and Culture, 13(2), 64.

http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.X.X.2018.pXXXX www.ijsrp.orgInternational Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume X, Issue X, December 2025 9

ISSN XXXX-XXXX

5. Haarmann, H. (2008). “The Danube Script and its Legacy: The

Cradle of Literacy in Prehistoric Europe.” The Journal of

Archaeomythology, 4(1).

6. Wikipedia Contributors. “Dispilio Tablet.” Accessed October

2025.

7. Wikipedia Contributors. “Vinča symbols.” Accessed October

2025.

8. Wikipedia Contributors. “Proto-writing.” Accessed October

2025.

9. Wikipedia Contributors. “Early world maps.” Accessed

October 2025.

10.Wikipedia Contributors. “Lake Orestiada.” Accessed October

2025.

11.Wikipedia Contributors. “Kastoria.” Accessed October 2025.

12. Kokkinidis, T. (2024, September 1). “Dispilio Tablet, The

Earliest Written Text Discovered in Greece.” Greek Reporter.

13. Snow, D., & History Hit Editorial Team. (2022, November

13). “The Saint-Bélec Slab: The Oldest Map in Europe.”

History Hit.

14. Thiry, M., & Milnes, A. (Reported by Archaeology Magazine

Staff). (2025, October 16). “World’s oldest 3D map, dating

back to 18,000 BCE, discovered in a Paleolithic cave near

Paris.” Archaeology Magazine. (Note: Refers to the Ségognole

3 discovery).

15. Thiry, M., & Milnes, A. (Reported by Ancient Origins Staff).

(2025, October 14). “World’s Oldest 3D Map (from 18,000

BC) Found in Cave Near Paris.” Ancient Origins.

16. Visit Greece Editorial Team. “Dispilio of Kastoria.” Visit

Greece.

17. Discover Kastoria Staff. “Lake settlement of Dispilio.”

Discover Kastoria.

18. Neolithic Avgi Project Team. “The technology of house

construction at the Neolithic settlement of Avgi.” Neolithic

Avgi.

19. Simon Fraser University Museum of Archaeology and

Ethnology Curators. “Engraving and Incising Tools.”

20. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History Curators.

“Early Stone Age Tools.”

21. PBS NOVA Editorial Team. “A Stone Age Toolkit.” PBS

NOVA Online.

22. Hitchcock, D. “Stone Tools.” Don’s Maps.

23. Austrian Academy of Sciences (OREA Institute). “Neolithic

Imagery.”

24. Cabej, N. “The Faith of the Neolithic Inhabitants of the

Western Balkans.” Gazeta Dielli.

25. Siebold, J. “The Earliest Known Map.” Myoldmaps.com.

26. Delano Smith, C. “Prehistoric Maps.” In J. B. Harley & D.

Woodward (Eds.), The History of Cartography, Volume 1.

University of Chicago Press.

27. Daidalika Editorial Team. “Neolithic Scripts.” Daidalika.

28. Janke, R. V. (2016, August 21). “The so-called (invalid)

relationship between the markings on the Neolithic Dispilio

tablet and some of the syllabograms in Mycenaean Linear B.”

Minoan Linear A and Mycenaean Linear B (WordPress blog).

29. Rossis, N. (2020, November 10). “The Dispilio Tablet:

Revising the Origins and Development of Writing.”

Nicholasrossis.me.

30. The Archaeologist Staff. “Dispilio Tablet: The Oldest Known

Written Text.” The Archaeologist.

31. Giroux, M. (High Heels and a Backpack). “Dispilio Tablet:

Could This 7,000-Year-Old Discovery Rewrite History?”.

Highheelsandabackpack.com.

32. Various Authors. Online discussions and video platforms

(e.g., Reddit, YouTube).

AUTHORS

First Author – Mavronicolas, Peter G., Master of Science in

Computer Science, Old Dominion University,

pete@reefsquid.com.olas